Antarctic plant life

Plant life

Plant life, or primary producers, on Antarctica are dominated by a different set of organisms than we typically see around us. The vegetation is dominated by mosses, lichens, liverworts and algae and there are currently only two native vascular plant species on Antarctica: the grass Deschampsia antarctica and the cushion plant Colobanthus quitensis. The main constraint for vascular plant presence in Antarctica is the climate and in particular the combination of infrequent water availability with very low summer temperatures. Nearly all vascular plant life on earth is adapted to some kind of seasonality, which allows them to maximize growth during the growing season, but this makes them vulnerable to the freezing and drying extremes that frequently occur during Antarctic growing seasons. Mosses, lichens and algae are well adapted to cope with large variation in freezing and drying conditions during the Antarctica growing season and are the dominant primary producers.

Biodiversity in Antarctica

Mosses

Mosses are an old lineage of land plants. They consist of a simple stem with small leaves attached and most are only a few centimeters in height. Moss leaves are typically only one cell width thick and have limited structure for uptake and transport of water and nutrients. This, in contrast to the land plants we most often see around us, like grasses and trees, that have developed various specialized structures for the uptake and transport of water and nutrients throughout their body.

Mosses are photosynthetic organisms, meaning that they can turn CO2 and H2O into sugar by using sunlight as an energy source. Due to the lack of specialized root structures mosses are dependent on precipitation, melt water or other external nutrient sources, for instance bird guano, to obtain sufficient nutrients for growth and reproduction. Currently about 250 species of mosses have been recorded across Antarctica with the largest species number at lower latitudes, where conditions are relatively warmer and wetter, while species numbers rapidly drop to below 30 in the interior of the cold and dry continent

What do mosses look like and what do they do?

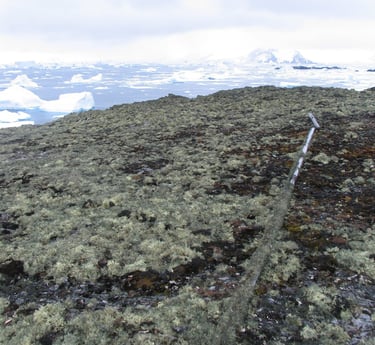

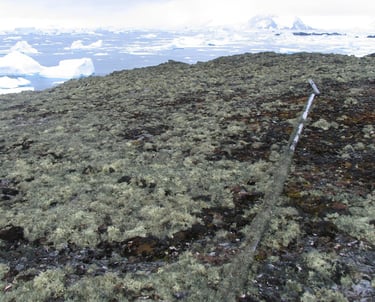

Mosses come in various shapes, colour and sizes depending on the species, the family they belong to and where they grow. Typically mosses are grouped according to the type of habitat they create. There are carpet forming mosses that can create an extensive cover of rather flat looking vegetation, that keeps spreading horizontally, but is often not more than a few centimetres thick. Turf forming mosses build up a layer of moss individuals that eventually can grow several meters thick. Finally there are cushion forming mosses that grow as small isolated clumps that look a bit like cushions.

Moss morphology plays a strong role in how they affect their surrounding environment for their own growth but also for associated fauna. Leaf shape and colour affects the amount of solar radiation captured or reflected. Darker mosses will absorb more solar radiation, thereby warming up faster than lighter coloured mosses. This warming speeds up photosynthesis but also creates a warmer environment for the activity of associated micro-organisms and invertebrates.

Lichens

A lichen is an organism consisting of a collaboration (symbiosis) of fungi and algae. The algal part photosynthesis and provides carbon for growth while the fungal part scavenges for essential minerals and nutrients. There is no fixed body plan and lichens come in various shapes and sizes. The fungal part can attach to and even grow into rock, where by scavenging for minerals, starts weathering the rock and initiates the first steps of soil formation.

Currently about 250 species of lichens have been recorded across Antarctica with the largest species number at lower latitudes, where conditions are relatively warm and wet, while species numbers decline to about 150 in the interior of the cold and dry continent

What do lichens look like and what do they do?

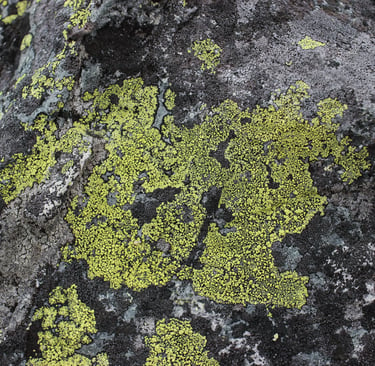

Morphologically we can separate lichens into three groups; 1) crustose lichens which are flat and strongly adhered to the surface they grow on, which can be rock, on top of moss or any man-made structure when present. 2) foliose lichens, which have a somewhat leaf like shape, are adhered to a substrate at a single point. 3) fruticose lichens which look similar to miniature shrubs grow into a complex three dimensional structure. Of course there are various species that morphologically fall between these three classifications.

Lichens are very well adapted in coping with infrequent water availability and low temperature, one of the reasons why lichens are so successful in Antarctica. Where a vascular plant would wilt after prolonged drought and experience freezing damage after repeated freezing and thawing, lichens simply stop and resume physiological activity depending on their water status with minimal impact on survival and growth.

Lichens are among the first colonizers of most terrestrial ecosystems on Earth and also play this role in Antarctica. However, Antarctic lichens are not out competed by secondary colonizers, such as grasses and shrubs, due to the near complete absence of vascular plants, and this is one of the unique aspects of Antarctic terrestrial ecosystems.

Algae

Algae comprise various groups, including single cell organisms or more complex multicellular organisms, such as kelp and seaweeds. On land most algae are present as single cell organisms and some that form mats. As photosynthetic organisms, algae can use sunlight, CO2 and water to create sugars, so as long as there is sufficient water and some sunlight it is possible to find some kind of algal growth. Algae do not have leaves, stems or roots and the physical appearance on land is shaped by the habitat.

The most visible terrestrial algae in Antarctica is Prasiola crispa, which can create extensive surface cover across tens of square meter along coastlines and across moss vegetation. Prasiola crispa can appear suddenly under the right conditions, but is quickly blown away when dry, so is not considered a permanent vegetation structure like a moss carpet or lichen community. Snow algae, are mostly singe celled algae that thrive in the snow and are visible because they colour the snow green and red. Snow algae can spread widely across snow fields and glaciers, to such an extent that this is visible through satellite in outer space. In damp spots underneath rocks there is often a thin layer of algae present and these can consist of various species.