Biogeography

Biogeography

Biogeography is the science that describes and aims to predict species distribution patterns. For Antarctic terrestrial biology there are clear declines in species richness from northern regions to southern colder ones. However, there is large variation across regional and local scales, so scale matters when interpreting species patterns.

Continental

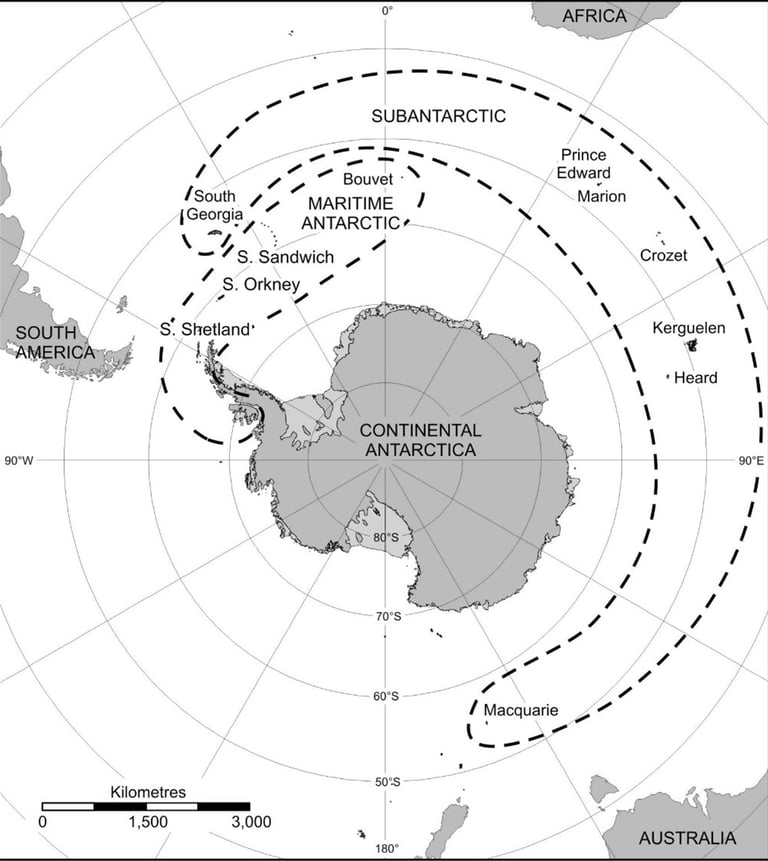

Classical Antarctic terrestrial geographic regions consisted of sub-Antarctic islands, the maritime Antarctic, comprising the Antarctic Peninsula and neighbouring islands, and the Antarctic continent. The sub-Antarctic islands form stepping stones between the Antarctic continent and neighbouring landmasses; South America (1000 km from the Peninsula), South Africa and Australia (4000-5000 km from the continent), and therefore, support many vascular plants, insects and invertebrates that can often also be found at these more northern regions. Further south, along the Antarctic Peninsula, vegetation is dominated by mosses and lichens with a much smaller groups of associated insects and invertebrates. The continent region comprises the mainland and supports much lower overall biodiversity.

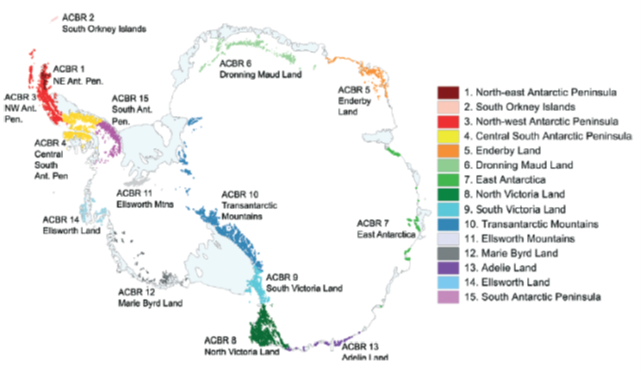

However, these classical regions, while useful, are now divided into 16 distinct biological regions as biogeographic studies have identified that there are regional differences in species composition. These new regions are now named: Antarctic Biogeographic Conservation Regions (ABCR) with the intent to clarify that each of those supports a unique biodiversity and that they each require their own environmental protection strategy.

Classical Antarctic biogeographic regions

Antarctic Biogeographic Conservation Regions

Regional

Antarctic ice free regions are separated by extensive glaciers or ocean, which makes it hard for small invertebrates like springtails and mites to cross from one region to another. Mosses, lichens and algae can be dispersed by wind across seawater and glaciers and establish on new locations.

Antarctic terrestrial habitats are surrounded by glaciers and ocean, making it hard for organisms to migrate to other regions

Mountain peaks surrounded by glaciers are island refuges for terrestrial biota.

Antarctic terrestrial habitats are surrounded by glaciers and ocean, making it hard for organisms to migrate to other regions

Local

At a local scale (m - km) species patterns are primarily driven by water and nutrient availability. Water is scarce in Antarctica as most of it is locked in ice, and therefore, inaccessible for use by plants and animals. Most plant life in Antarctica can be found thriving near melt streams and snow fields, especially mosses often depend on such water sources for survival and growth and therefore grow nearby readily available water sources. Lichens are more hardy and often rely on air humidity. Nevertheless, lichens do not grow everywhere, as some species are vulnerable to snow cover and avoid growing in areas with a thick winter snow pack. Other lichens thrive on bare rock but are easily out-competed by taller lichens.

Moss communities thrive where there is frequent or persistent water available.

Terrestrial algae (Prasiola crispa) can lie dormant for long periods and is quickly re-activated when liquid water becomes available.

Moss communities can be very small. Much of Antarctic vegetation consists of very many tiny patches of moss and lichen communities

Lichen fell-fields support extensive fields of various lichen species. Mostly on dry and wind exposed habitats

Terrestrial algae (Prasiola crispa) can form extensive fields under the right conditions, but can quickly disappear under dry and windy conditions

Landscape filled with moss communities (Byers Peninsula - Livingston Island)

Species interactions

Terrestrial animals are dependent on the plant life for food, but plants also provide shelter against harsh weather conditions. Mosses typically grow in wet places, but can also retain a lot of water for long periods, so any animal that is vulnerable to drought will benefit from living within a moss habitat. Springtails typically thrive very well among mosses and can reach densities of up to 1 million individuals per square meter of moss. Similarly, the algal mats crated by Prasiola crispa can support high numbers of springtails due to the microclimate but also because the algal mat is used as a food source by springtails.

The mites living in Antarctica have a thick outer shell and are well suited to cope with dry conditions. This is probably one of the reasons why they thrive well among lichen fell fields, where they consume algae, lichens or prey upon other animals.

Not all Antarctic terrestrial animals are associated with plant life and instead are more often found underneath rocks, where they find shelter against dehydration, frost and UV light. They most likely feed on microbial mats or algal growth at the rock edge.

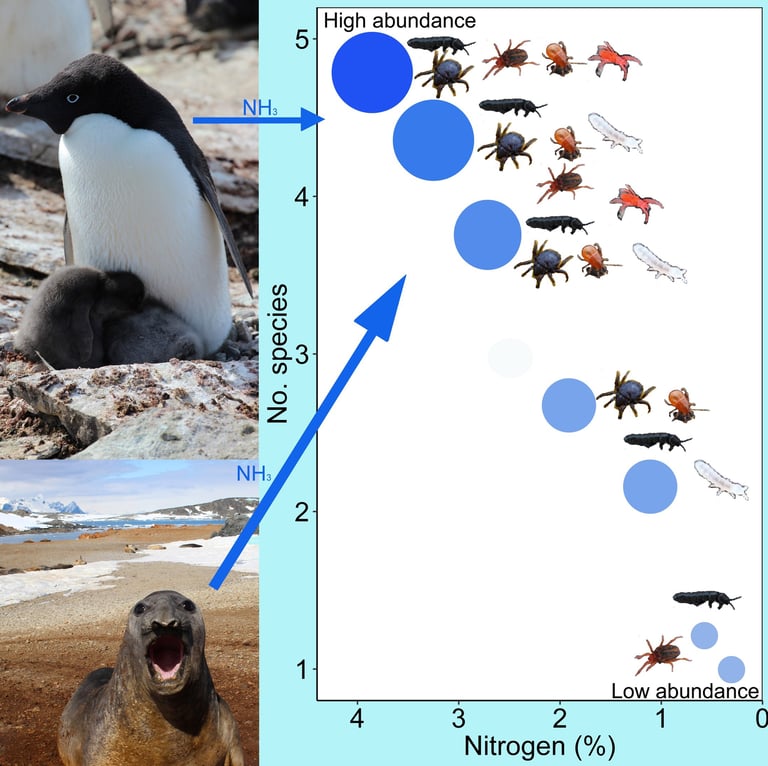

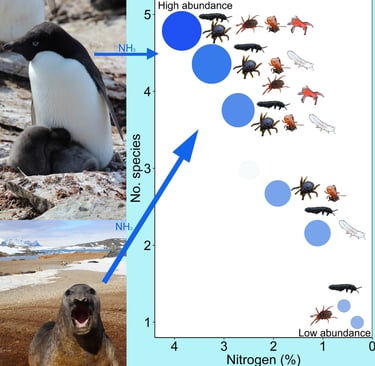

Nutrients

Antarctic vegetation is highly enriched in nutrients nearby penguin colonies but not all species thrive under such severe nutrient loadings and moss and lichen diversity and biomass peaks at some distance from bird and seal aggregations. The nutrient enrichment of the mosses and lichens also affects the associated animals with higher species numbers and abundance, as they provide a more nutritious food source, compared to areas outside the influence of penguins and seals. Penguins and seals are an important nutrient factor from the sea to land and create biodiversity hotspots of terrestrial biota.

Springtail and mite abundance and species richness is enhanced by the nutrient input from penguins and elephant seals

Most lichens and mosses cannot thrive near penguin colonies due to high nitrogen loading, but orange coloured lichens like Xanthoria benefit from the additional nutrients.

Mapping vegetation

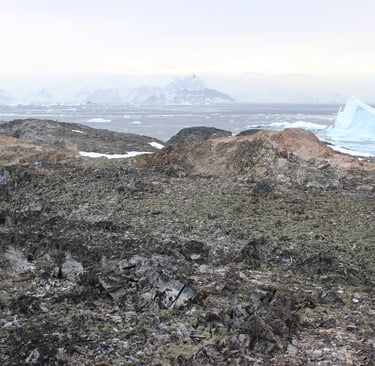

Biogeography deals with the patterns of species populations, so this requires knowledge on the spatial cover or number of individuals of organisms. Because most of Antarctica is covered by snow or ice and only small patches of moss and lichen cover exist at ice-free locations the distribution of vegetation is very patchy, making it hard to quantify how much there actually is. On top of that, most locations are hardly ever visited or are inaccessible. Recent attempts at quantifying Antarctic vegetation using satellites indicates that there is likely more than 30 square kilometres of green vegetation and approximately 8 square kilometres of lichen cover. However, this is most likely a great underestimation as mosses do not always reflect light in the same manner, due to differences in water status, and this can affect whether a satellite can detect it as green vegetation or not. Lichens are even harder to detect and distinguish from bare rock as they are most often not active when satellites have a clear view of the ground (no clouds and sunny weather is good for satellite observations but lichens will be dehydrated, not active, and harder to distinguish from rocks). In addition, many mosses and lichens grow as small clumps of 10 cm by 10 cm which may not be detectable by typical satellites.

While Antarctic biology and biogeography has been studied for many decades, we are still struggling to accurately quantify how much vegetation grows on Antarctica. Further, while it is clear that the great variety of moss and lichen communities support unique associations of springtails, mites, netmatodes, tardigrades and microbes, we are still far from establishing base-line population counts for these Antarctic terrestrial animal groups. This knowledge is vital if we want to protect Antarctic biodiversity and make predictions on impacts of climate change, threats of non-native species and human activities.

A barren landscape or not? This is an overview image of Lagoon Island (Marguerite Bay) and may appear devoid of life but is actually completely covered by a rich lichen carpet.

Antarctic fell field community with various fruticose and crustose lichens (Lagoon Island)

Antarctic moss community where free flowing water gathers (Lagoon Island)

Antarctic fell field close-up with various fruticose and crustose lichens (Lagoon Island)

Moss growing among fractured rock. Black dots on rock surface are crustose lichens (Lagoon Island)

Want to know more...

A selection of resources on Antarctic Biogeography

Convey, P., Chown, S. L., Clarke, A., Barnes, D. K. A., Bokhorst, S., Cummings, V., Ducklow, H. W., Frati, F., Green, T. G. A., Gordon, S., Griffiths, H. J., Howard-Williams, C., Huiskes, A. H. L., Laybourn-Parry, J., Lyons, W. B., McMinn, A., Morley, S. A., Peck, L. S., Quesada, A., Robinson, S. A., Schiaparelli, S. and Wall, D. H. 2014. The spatial structure of Antarctic biodiversity. Ecological Monographs, 84, 203-244.

Convey, P. and Biersma, E. M. (2024). Antarctic Ecosystems. Encyclopedia of Biodiversity S. S.M. Oxford, Elsevier. 1: 133-148.

Bokhorst, S., Convey, P. and Aerts, R. 2019. Nitrogen inputs by marine vertebrates drive abundance and richness in Antarctic terrestrial ecosystems. Current Biology, 29, 1721-1727.

Many of the above documents are freely available from the publisher websites, but if not, please feel free to reach out to the authors for a copy